“The Only Thing That Is Constant Is Change” -Heraclitus

Introduction

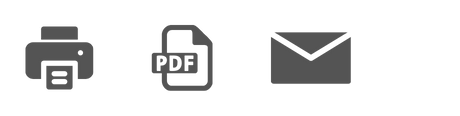

Have you ever wondered why some herbal remedies seem to work so well? The answer might surprise you—it’s not just the plant itself, but a remarkable partnership between the plant compounds and the trillions of microorganisms living in your gut microbiome. These microbes—comprising over 1,000 species of bacteria, fungi, and other organisms—do far more than help digest food.1

They function as sophisticated biochemical factories, transforming plant phytochemicals into bioactive metabolites that your body can effectively utilize.2 This process, known as biotransformation, can significantly enhance the therapeutic potential of many traditional plant medicines.

For centuries, traditional healing practices across cultures have recognized the medicinal power of plants, from chamomile and echinacea to turmeric and ginger. Modern science is now revealing the sophisticated mechanisms behind these ancient remedies: bioactive compounds in plants interact with our gut microbiome—that diverse community of bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms inhabiting our digestive tract—creating a complex dialogue that influences our overall health in profound ways.

Plants and microorganisms within our gut coexist within intricate ecosystems, engaging in sophisticated molecular dialogues that generate novel compounds with healing properties. This intricate relationship represents one of nature’s most elegant examples of cross-kingdom communication, where plant chemistry meets microbial metabolism to modulate our immune system, mental health, and metabolic processes. This symbiotic relationship creates a complex network of genetic, biochemical, physical, and metabolic interactions between plant compounds and our gut’s microbial ecosystem.3

Every herb can have a multitude of active compounds, each one able to communicate with several target proteins with a high number of protein-to-protein responsive interactions (high biological network connectivity) and that these protein targets have higher network connectivity than disease genes. Proteins play a pivotal role in many biological processes.

Much like skilled jazz musicians improvising together to create harmonious music, these biological entities respond to and build upon each other’s chemical signals, creating a dynamic equilibrium that significantly impacts human health.

Research increasingly demonstrates that plant-based compounds, such as polyphenols and flavonoids, undergo transformation by gut bacteria into bioactive metabolites with enhanced therapeutic potential. These metabolites can modulate inflammation, strengthen intestinal barriers, and even influence neural signaling pathways, highlighting the profound connection between dietary choices and physiological wellness.

“Nature is a totally efficient, self-regenerating system. If we discover the laws that govern this system and live synergistically within them, sustainability will follow and humankind will be a success.” –Buckminster Fuller

The Hidden World Within Plants

Every plant hosts a complex ecosystem invisible to the naked eye. Similar to the human microbiome, plants maintain vital relationships with internal microbial partners that influence their health and development. These endophytes—microorganisms that live within plant tissues without causing disease—which Dr. Sarah Martinez calls “nature’s original genetic engineers,” have supported plant life since vegetation first colonized land over 450 million years ago.

Research from the Global Plant Sciences Initiative reveals that individual plants host hundreds of endophyte species, each playing specialized roles in supporting their host’s survival. “We’re uncovering sophisticated chemical dialogues between plants and their microbial partners that regulate everything from nutrient acquisition to pest resistance,” notes Dr. James Chen of the Agricultural Biotechnology Center.

Recent studies by Rodriguez et al. (2019) demonstrated that certain fungal endophytes can confer drought tolerance to agricultural crops by altering plant hormone signaling pathways. This discovery has profound implications for sustainable agriculture in regions facing increasing water scarcity due to climate change. As Rodriguez writes, “The manipulation of plant-endophyte relationships represents one of our most promising frontiers for addressing food security challenges in the 21st century.“4

Secondary Compounds in Plants: Mediators of Gut Microbiome Transformation and Therapeutic Potential

The evolutionary development of plants and their intricate relationships with other organisms has led to the production of numerous complex secondary compounds. Plants contribute significantly to Earth’s terrestrial biomass, representing more biomass by volume and weight than all other life forms combined.5

Plants have evolved these medicinal properties through three primary mechanisms. First, they synthesize compounds structurally analogous to those found in human physiology—molecules that can interact with our cellular receptors and signaling pathways with remarkable specificity. Second, these specialized biomolecules are strategically accumulated within plant tissues—roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits—where they remain stable until extraction and utilization in traditional or modern medical applications. Third, once introduced to the human body, these phytochemicals can effectively mimic, modulate, or enhance the activities of our endogenous biomolecules, thereby catalyzing healing processes and promoting homeostasis.6

Like jazz music, the herbs within our ecosystem create dynamic streams of energy, rising and falling in rhythmic succession. They diverge and converge, intertwine and separate, ultimately harmonizing to create a balanced symphony that sustains and nourishes the entire living community. – Donnie Yance

Adaptive Strategies of Plants

Due to their immobile nature, plants have evolved sophisticated adaptive mechanisms for survival. These adaptations address several critical challenges:

- Engineering their own pollination and seed dispersal mechanisms

- Acquiring nutrients within their immediate environment

- Defending themselves against predators and pathogens, as they cannot physically escape threats

- Plant compounds are transformed by gut microbes into bioactive substances that affect health and disease.

Plants have developed complex relationships with herbivores and pathogens in their environment that might otherwise overwhelm them. Through evolutionary processes, plants have developed secondary biochemical pathways that enable the synthesis of various chemical compounds in response to specific environmental stimuli, such as herbivore damage, pathogen attacks, or nutrient deprivation.7 These secondary metabolites can be species-specific or broadly distributed across plant families.

I often refer to the secondary metabolites in medicinal herbs and foods as bathing our bodies with nano nutrition. These bioactive compounds—including polyphenols, alkaloids, and terpenes—interact with our cellular machinery at microscopic levels, delivering targeted therapeutic effects without the harsh side effects of synthetic pharmaceuticals. This remarkable system of natural compounds has evolved over millions of years, creating a sophisticated language of biochemical communication between plants and the organisms that consume them.

Functional Roles of Plant Secondary Compounds

Secondary compounds significantly enhance a plant’s survival by facilitating interactions with its environment. Their roles include:

- Providing general protective functions (antioxidant, free radical-scavenging, UV light absorption)

- Defending against microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, viruses)

- Establishing competitive advantages against neighboring plants

- Attracting beneficial organisms while deterring harmful ones.89

Plant Secondary Compounds and Human Health

Research increasingly demonstrates that when humans consume plants containing these secondary compounds, either as whole foods or medicinal extracts, these compounds can enhance our resilience to various stressors. This occurs through multiple mechanisms:

- Cellular protection against oxidative damage10

- Adaptive stress responses11

- Enhanced immune function12

- Epigenetic repair and regulation.13

The Gut Microbiome as a Metabolic Transformer

A critical but often overlooked aspect of plant medicine efficacy involves the gut microbiome’s role in biotransformation. When plant compounds enter the digestive system, resident microbiota metabolize these substances, often converting them into novel compounds with enhanced bioavailability and therapeutic properties.14 This microbiome-mediated transformation creates:

- New bioactive metabolites that are not present in the original plant material15

- Compounds with improved absorption profiles16

- Molecules capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier17

- Signaling compounds that modulate immune and inflammatory responses.18

The gut microbiome essentially functions as a secondary metabolic organ, completing the transformative process that begins in the plant and culminates in the human body.19 This symbiotic relationship between plants, microbes, and humans represents an intricate evolutionary development that modern medicine is only beginning to understand and leverage therapeutically.20

The Plant-Human Connection

When you consume medicinal herbs or plant-based foods, something magical happens:

- The Transformation Process: Your gut microbes break down plant compounds that your body couldn’t otherwise use, turning them into powerful active molecules that can enter your bloodstream.

- Two-Way Relationship: Plants don’t just get transformed—they can actually change your gut community itself! Certain herbs can encourage beneficial microbes to flourish while discouraging harmful ones.

- Custom Medicine: This process is incredibly personal. Your unique gut community might transform the same herb differently than someone else’s would—which helps explain why traditional medicines might work differently for different people.

The Bigger Picture

This relationship reveals something profound about our connection to the plant world. We didn’t just evolve alongside plants—we evolved with them as partners. Our bodies aren’t isolated systems but are designed to work in concert with both plants and microbes in a beautiful ecological relationship.

The next time you sip that herbal tea or take a plant-based supplement, remember: you’re not just consuming a plant—you’re activating an ancient partnership between plants, microbes, and your body that has been refined over millions of years of evolution.

Medicinal herb-derived natural products and the gut microbiota. The gut microbiota mediates the biosynthesis and biotransformation of natural products derived from medicinal herbs to impact both health and disease. Figure created with Biorender.com; URL accessed on 19 July 2024.21

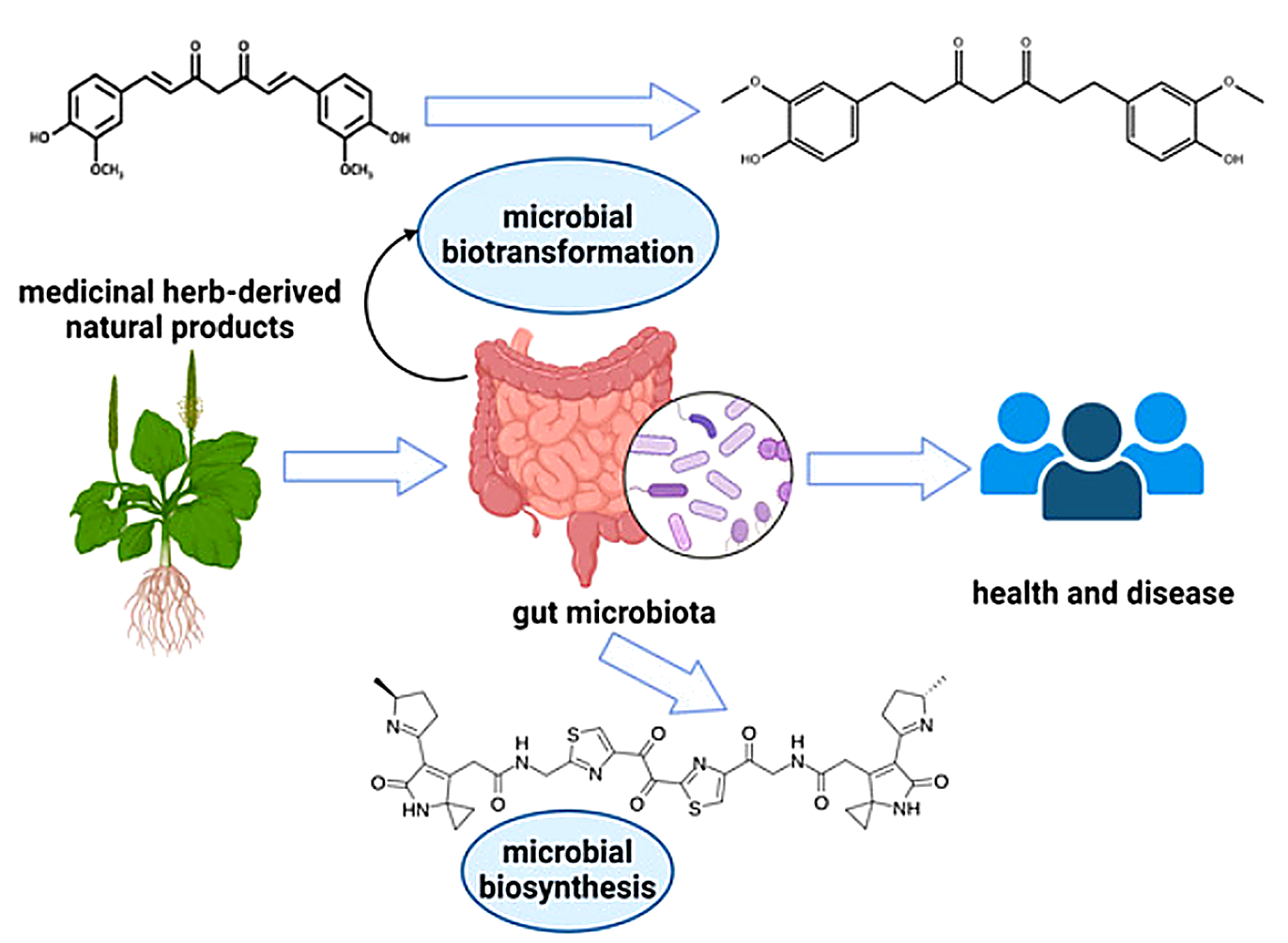

Curcumin and the Microbiome: Creating Therapeutic Metabolites

Curcumin is the main active molecule found in turmeric root. Curcumin presents a fascinating paradox in therapeutic research: despite poor bioavailability, it demonstrates remarkable pharmacological effects. The explanation lies not in the compound itself, but in its transformation.

The human gut microbiota plays a crucial role in curcumin’s efficacy by facilitating chemical transformation of the compound. This process is not merely a degradation but a necessary activation step that creates bioactive metabolites with enhanced therapeutic properties.

Recent research reveals that gut microbiome-mediated degradation products—including: ferulic acid, ferulic aldehyde, vanillin, and vanillic acid—achieve significantly higher concentrations in the body than curcumin itself. These metabolites demonstrate superior biological activity, including:

- Enhanced oxygen radical scavenging capabilities

- Stronger inhibition of amyloid-beta formation

- Improved enzymatic interactions

When curcumin is ingested, it undergoes phase I metabolism to form several active metabolites—including dihydrocurcumin, tetrahydrocurcumin, hexahydrocurcumin, and octahydrocurcumin. During this metabolic process, the body also produces degradation compounds like ferulic acid and bicyclopentadione. While these phase I metabolites demonstrate beneficial biological activity, the phase II metabolites that form afterward—such as curcumin glucuronides and sulfates—have proven ineffective in independent studies.22

In vivo studies confirm that these microbial metabolites, rather than unchanged curcumin, are the predominant compounds in circulation after consumption. This microbiome-dependent transformation explains why curcumin’s therapeutic effects exceed what its poor bioavailability would suggest.

Understanding this gut microbiota-curcumin interaction provides a new framework for developing targeted formulations that optimize these beneficial transformations rather than focusing solely on delivering intact curcumin to the bloodstream.23

Conclusion

Our bodies are part of a much bigger system—one where plants, microbes, and humans work together in harmony. Medicinal plants aren’t just powerful on their own; they rely on the help of the gut microbiome to unlock their full healing potential. These tiny microbes in our digestive system break down plant compounds and turn them into powerful substances that reduce inflammation, oxidation, and support our immune system, brain health, and overall wellness.

This partnership between plants and microbes is like an improvised jazz piece—each part working with the others to create something greater than they could alone. By eating a diet rich in herbs, plant-based foods, fermented products, and probiotics, we’re not just nourishing our bodies; we’re also supporting a natural process that’s been evolving for millions of years.

As science continues to uncover how deeply connected we are to the plant world, one thing becomes clear: good health doesn’t come from isolated ingredients, but from the glorious cooperation between nature, microbes, and the human body.

The underlying philosophy of Traditional Herbal Medicine expresses the basic premise that healing comes from the wisdom of God, and it is inherently found in Nature (Gaia). This spiritual wisdom dwells within all human beings. For me, working with herbs as medicine has taken my spirit to a deep philosophical reflective place and given me insights into the revelations of our Creator – showing me the face of God.

- Valdes, A. M., Walter, J., Segal, E., & Spector, T. D. (2018). Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ, 361, k2179. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2179

- Chen, F., Wen, Q., Jiang, J., Li, H. L., Tan, Y. F., Li, Y. H., & Zeng, N. K. (2016). Could the gut microbiota reconcile the oral bioavailability conundrum of traditional herbs? Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 179, 253-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.12.031

- Bisht, N., Singh, T., Ansari, M.M. et al. The hidden language of plant-beneficial microbes: chemo-signaling dynamics in plant microenvironments. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 41, 35 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-025-04253-6

- Rodriguez, R.J., White, J.F., Arnold, A.E., & Redman, R.S. (2019). Fungal endophytes: Diversity and functional roles in plant drought tolerance. New Phytologist, 182(2), 314-330.

- Pimentel, D., & Andow, D. A. (1984). Pest-management and pesticide impacts. Insect Science and Its Application, 5(3), 141-149.

- Wink, M. (2015). Modes of action of herbal medicines and plant secondary metabolites. Medicines, 2(3), 251-286. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines2030251

- Hartmann, T. (2007). From waste products to ecochemicals: fifty years research of plant secondary metabolism. Phytochemistry, 68(22-24), 2831-2846.

- Kennedy, D. O., & Wightman, E. L. (2011). Herbal extracts and phytochemicals: plant secondary metabolites and the enhancement of human brain function. Advances in Nutrition, 2(1), 32-50.

- Wink, M. (2018). Plant secondary metabolites modulate insect behavior-steps toward addiction? Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 364.

- Scalbert, A., Manach, C., Morand, C., Rémésy, C., & Jiménez, L. (2005). Dietary polyphenols and the prevention of diseases. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 45(4), 287-306.

- Calabrese, E. J., Mattson, M. P., & Calabrese, V. (2010). Resveratrol commonly displays hormesis: occurrence and biomedical significance. Human & Experimental Toxicology, 29(12), 980-1015.

- Jantan, I., Ahmad, W., & Bukhari, S. N. A. (2015). Plant-derived immunomodulators: an insight on their preclinical evaluation and clinical trials. Frontiers in Plant Science, 6, 655.

- Li, Y., & Tollefsbol, T. O. (2010). Impact on DNA methylation in cancer prevention and therapy by bioactive dietary components. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 17(20), 2141-2151.

- Clavel, T., Borrmann, D., Braune, A., Doré, J., & Blaut, M. (2006). Occurrence and activity of human intestinal bacteria involved in the conversion of dietary lignans. Anaerobe, 12(3), 140-147.

- Possemiers, S., Bolca, S., Verstraete, W., & Heyerick, A. (2011). The intestinal microbiome: a separate organ inside the body with the metabolic potential to influence the bioactivity of botanicals. Fitoterapia, 82(1), 53-66.

- Laparra, J. M., & Sanz, Y. (2010). Interactions of gut microbiota with functional food components and nutraceuticals. Pharmacological Research, 61(3), 219-225.

- Westfall, S., & Pasinetti, G. M. (2019). The gut microbiota links dietary polyphenols with management of psychiatric mood disorders. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 1196.

- Ozdal, T., Sela, D. A., Xiao, J., Boyacioglu, D., Chen, F., & Capanoglu, E. (2016). The reciprocal interactions between polyphenols and gut microbiota and effects on bioaccessibility. Nutrients, 8(2), 78.

- Koppel, N., Maini Rekdal, V., & Balskus, E. P. (2017). Chemical transformation of xenobiotics by the human gut microbiota. Science, 356(6344), eaag2770.

- Thaiss, C. A., Zmora, N., Levy, M., & Elinav, E. (2016). The microbiome and innate immunity. Nature, 535(7610), 65-74.

- Peterson, C.T. Gut Microbiota-Mediated Biotransformation of Medicinal Herb-Derived Natural Products: A Narrative Review of New Frontiers in Drug Discovery. J 2024, 7, 351-372. https://doi.org/10.3390/j7030020

- Majeed M. The Age of Biotransformation, 2015; Personal communication. Ganjali S, Sahebkar A, Mahdipour E, Jamialahmadi K, Torabi S, Akhlaghi S, Ferns G, Parizadeh SM, Ghayour-Mobarhan M. The Scientific World Journal 2014; doi 10.1155/2014/898361

- Majeed M. The Age of Biotransformation, 2015; Personal communication. Ganjali S, Sahebkar A, Mahdipour E, Jamialahmadi K, Torabi S, Akhlaghi S, Ferns G, Parizadeh SM, Ghayour-Mobarhan M. The Scientific World Journal 2014; doi 10.1155/2014/898361