Grains are the most important source of food on our planet, providing nearly 50% of the caloric needs of cultures around the world. Fortunately, grains also happen to be among the least intensive foods to produce. Along with environmental sustainability, grains provide significant health benefits.

According to the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, “consistent evidence indicates that, in general, a dietary pattern that is higher in plant-based foods, such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds, and lower in animal-based foods is more health promoting and is associated with lesser environmental impact.” 1

The 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee goes on to say, “meeting current and future food needs will depend on two concurrent approaches: altering individual and population dietary choices and patterns and developing agricultural and production practices that reduce environmental impacts and conserve resources, while still meeting food and nutrition needs.” 2

As scientists assess the risks and benefits of different food production systems, it is easy to see why grains have been at the core of traditional diets for millennia. Fruits and vegetables, while highly nutritious, aren’t as energy dense as grains and are harder to grow, transport, and store for year-round enjoyment.

How Your Food Choices Affect Climate Change

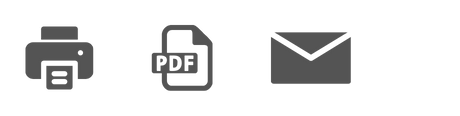

Food production and consumption are important considerations when addressing climate change. Today’s industrial food production contributes significantly to environmental degradation. Meat production accounts for the largest impact, including greenhouse gas emissions along with excessive land and water use.

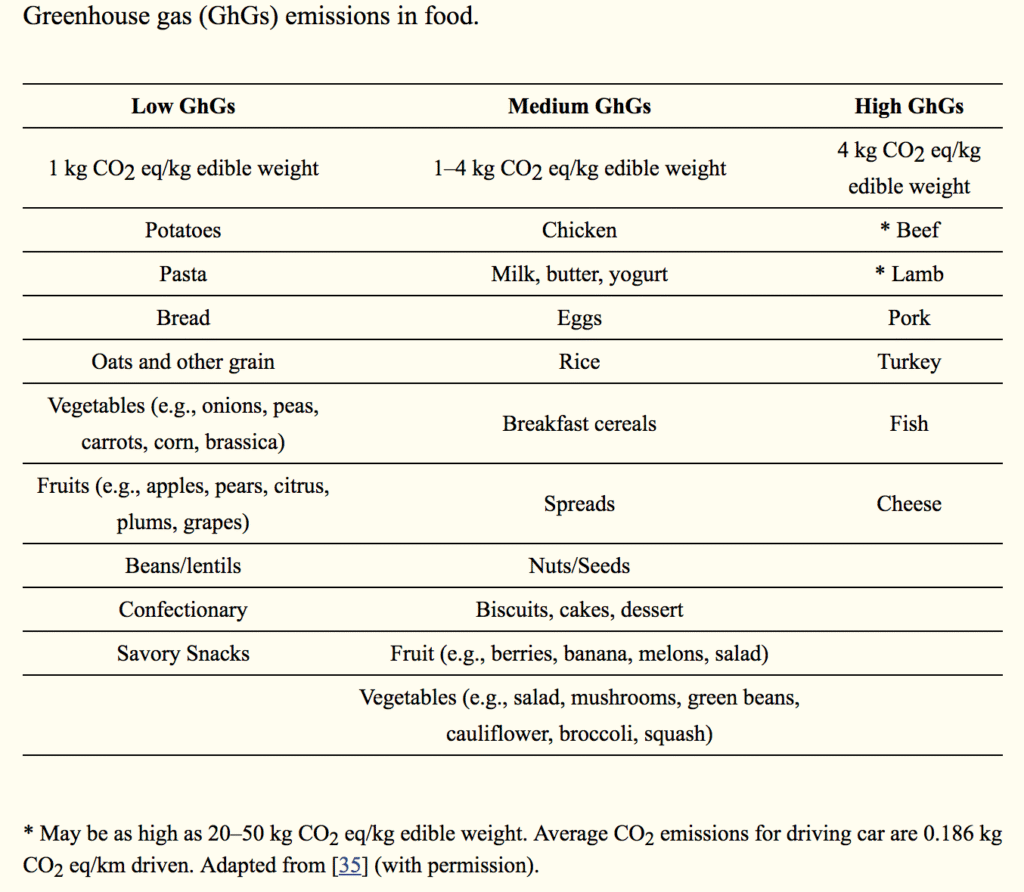

We need to consider dietary changes that promote health for people and the planet. In the past decade, healthful and sustainable dietary recommendations have been promoted by various governmental agencies. However, resistance persists when it comes to suggested reductions in meat consumption.

Change comes through education and understanding, and we must move from being food consumers to food citizens. According to Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and Center for a Livable Future, a food citizen understands the wide-reaching effects of his or her food decisions, and among other socially and environmentally conscious decision-making, makes dietary choices based on the origin of a food, how it is produced, and who is producing it.

Adapted from “Eat As If You Could Save The Planet And Win!” Sustainability Integration into Nutrition for Exercise and Sport, by N. Meyer, A. Reguant-Closa, 2017, Nutrients, 9, 412; doi:10.3390/nu9040412.

Why Whole Grains are the Perfect Food for a Sustainable Diet

As climate change makes weather patterns more extreme and unpredictable, our food supply will require a variety of grains that are adapted to diverse climates. I recommend exploring the world of “ancient” and “heirloom” whole grains. Ancient grains include wheat varietals such as einkorn, emmer/farro, freekeh, khorasan wheat (Kamut), and spelt; other grains such as barley, oats, rye, sorghum, and teff; and the pseudocereals amaranth, buckwheat, millet, quinoa, and wild rice.

What we know as wheat is actually modern wheat, and it is not an ancient grain, while einkorn, emmer/farro, Kamut®, and spelt are considered ancient grains in the wheat family.

The following are popularly considered to be “ancient grains”:

- Amaranth: domesticated about 8,000 years ago by the Aztecs.

- Farro: (also known as emmer): an ancestor of modern wheat, domesticated in the Fertile Crescent about 8,000 years ago. The name farro applies to a version grown in Italy.

- Freekeh: green wheat that has been roasted. It is often included with ancient grains but is the same species as modern wheat.

- Kamut: a trademarked variety of khorasan wheat, a relative of modern wheat.

- Millet: domesticated in China, now also commonly grown in India and several African countries including Nigeria.

- Quinoa: first grown at least 3,000 years ago in South America, the burgeoning US popularity is causing major economic changes for Bolivian growers.

- Spelt: another relative of wheat from the Fertile Crescent grown in Europe through medieval times.

- Teff: a grass with tiny seeds, domesticated and still grown in Ethiopia.

Many ancient grains thrive with lower levels of pesticides, fertilizers, and irrigation, offering an advantage in our current world situation of accelerating climate change. Rotating a diverse array of grain crops rather than growing in monoculture, as is done with modern grains, encourages agricultural practices that replenish the soil instead of depleting it.

Each grain has a unique nutrient profile, including vitamins, minerals, fiber, and phytonutrients.

The best way to ensure that you’re getting the full spectrum of nutrients is to eat a variety of grains—which also makes for an interesting, delicious, and budget-friendly diet.

The Current Fad Against Eating Wheat: And Why It’s Misguided

In the past decade, wheat has been demoted from the “staff of life” to a food that many people avoid. In his best selling book Wheat Belly, cardiologist Dr. William Davis calls modern wheat a “perfect, chronic poison” and places the blame on a gluten component called gliadin.3 Mark Sisson, who writes the blog Mark’s Daily Apple, argues that modern wheat has less selenium than ancient grains, and more of a supposedly harmful component of gluten.

But those claims don’t stand up to scrutiny. You’re not likely to have selenium deficiency, which is extremely rare, whether you eat wheat or not. Modern wheat doesn’t have significantly more gluten, and Dr. Davis’s wilder claims (like gliadin triggering opiod receptors) aren’t credible.

Avoiding wheat makes sense if you have celiac disease or if you feel like gluten-containing foods don’t agree with you. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity is controversial, but only in its cause—maybe it’s gluten, or perhaps FODMAPs (foods rich in fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols). These short chain carbohydrates are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and cause gas, bloating, stomach pain, diarrhea and constipation in susceptible individuals. No matter the cause, the symptoms are real, and it’s totally reasonable to avoid wheat if you feel better doing so.

There are many benefits to eating whole grains, including changes in the gut microbiome that improve metabolism and are associated with maintaining a healthy weight. Diets higher in plant fiber from whole grains appear to shift the ratio toward lower levels of Firmicutes and greater levels of Bacteroidetes. The benefits of this shift are under debate, but researchers propose that Firmicutes are associated with impaired gut barrier function and inflammatory responses that may lead to metabolic dysfunction and obesity. Increases in overall microbial diversity lead to overall beneficial effects, as some evidence suggests that lean individuals have a more diverse microbiota compared to obese individuals.4

Whole Grains Improve Gut Microbiome and Immune Health

Two clinical trials from Tufts University, published recently in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, show that substituting whole grains for refined grains, even for a short period, leads to “modest” improvements in the balance of microbes in the intestines (gut microbiome) along with improvements in aspects of the immune response and energy metabolism.

Both studies involved the same 81 healthy adults (ages 40 to 65), half of whom consumed a diet rich in whole grains (whole wheat, oats, and brown rice) for six weeks, while the rest ate refined grains. Other than the different forms of grains, the diets were virtually the same. All foods were provided in order to ensure that the diets kept body weight stable; participants were weighed three times a week and their diets were adjusted if they gained or lost weight. The whole grains provided about twice as much fiber (mostly insoluble fiber) as well as some extra nutrients and other potentially beneficial compounds.

Happier microbiome. In the first study, researchers assessed the effect of whole grains on the microbiome by analyzing the participants’ stool for bacterial content and concentration of fats. Previous research has shown that whole grains increase the variety of the microbiome and boost production of short-chain fatty acids, both of which are linked to immune function and digestive health. Along these lines, the whole-grain group in the new study showed an increase in bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids and a decrease in pro-inflammatory bacteria, among other positive changes, compared to those eating refined grains. What’s more, blood samples from the whole-grain group showed small improvements in several markers of a healthy immune response.5

Negating calories. The second study focused on changes in energy metabolism that could affect weight regulation. It found that whole grain consumption led to decreased calorie retention during digestion (as measured by calories in stool) and slightly higher resting metabolic rate—resulting in a net daily energy loss of 92 calories per day, on average, compared to the refined-grain diet. Self-reported hunger and fullness were not statistically different between the two groups. The additional fecal energy losses were due to the extra fiber’s effect on the digestion of other food calories, the researchers suggested.6

Whole Grains and Disease Prevention

A wealth of studies shows a direct correlation between whole grains and the prevention of various diseases. Colon cancer, one of the leading causes of cancer-associated deaths, is the target of choice for nutrition-based prevention approaches because of the direct and early contact between the active compounds and the cancerous tissues. In a 2018 study, researchers found that whole grain alkylresorcinols (ARs) induce apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest in human colon-cancer cells via activation of the p53 pathway.

The researchers had previously reported ARs as the major active components in wheat bran against human colon cancer. In this study, they further investigated the anticancer mechanisms of ARs. They reported that AR C15 and AR C17 exert their anticancer activities in colon-cancer cells by inducing apoptosis through PUMA upregulation and mitochondrial-pathway activation, inducing cell-cycle arrest through p21 upregulation, and inhibiting proteasome activity and Mdm2 expression. This cascade of distinct mechanisms was linked to the consequent activation and accumulation of p53. The results of treatment with p53 inhibitor further confirmed that the p53 pathway might play a very important role in AR-induced apoptosis in colon-cancer cells. The researchers concluded that AR C15 and AR C17 can specifically activate the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis and cause cell-cycle arrest and that inhibition of p53 greatly reduces the activation of this pathway.7

A 216 meta-analysis research study found a diet rich in whole grains is associated with a healthy and longer life. People who reported eating at least three servings of whole grains daily were 19% less likely to die early from any cause compared with people who reported eating less than one serving a day, the researchers found. The analysis included 14 previous studies; all of the studies were at least six years long, and many were more than 10 years long.

The researchers also looked at specific causes of death. They found that eating three servings of whole grains a day was associated with a 25 percent lower risk of death from heart disease, and a 14 percent lower risk of death from cancer, compared with eating one serving or less of whole grains daily.8

In addition, a 2018 meta-analysis study, which included 19 cohort studies with 1,041,692 participants and 96,710 deaths in total, concluded that each 28 g/d intake of whole grains was associated with a 9% lower risk for total mortality.9

From ancient times, grains have sustained and nourished us, and radical diets that encourage avoidance of all grains are shortsighted and misguided. I encourage you to include a variety of whole grains in your daily diet. It’s obvious from a wide array of scientific research in the realms of health and environmental sustainability that consuming whole grains is beneficial for us and good for the planet.

Resources

1. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee

2. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/PDFs/10-Part-D-Chapter-5.pdf

3. Davis, W. Wheat Belly: Lose the Wheat, Lose the Weight, and Find Your Path Back to Health, 2011, Rodale Books.

4. Danielle N. Cooper 1, Roy J. Martin 1,2 and Nancy L. Keim, Does Whole Grain Consumption Alter Gut Microbiota and Satiety? Healthcare 2015, 3, 364-392; doi:10.3390/healthcare3020364

5. Vanegas, S.M., et. al., Substituting whole grains for refined grains in a 6-wk randomized trial has a modest effect on gut microbiota and immune and inflammatory markers of healthy adults, Am J Clin Nutr October 2017 106: 1052-1061; First published online August 16, 2017. doi:10.3945/ajcn.117.155424

6. Karl, J.P. et. al., Substituting whole grains for refined grains in a 6-wk randomized trial favorably affects energy-balance metrics in healthy men and postmenopausal women Am J Clin Nutr ajcn139683; First published online February 8, 2017.

7. Fu J, Soroka DN, Zhu Y, Sang S. Induction of Apoptosis and Cell-Cycle Arrest in Human Colon-Cancer Cells by Whole-Grain Alkylresorcinols via Activation of the p53 Pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 2018 Nov 14;66(45):11935-11942. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b04442. Epub 2018 Oct 31.

8. Wei H, Gao Z, Liang R, Li Z, Hao H, Liu X. Whole-grain consumption and the risk of all-cause, CVD and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies, Br J Nutr. 2016 Aug;116(3):514-25. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516001975. Epub 2016 May 24.

9. Zhang B, Zhao Q, Guo W, Bao W, Wang X. Association of whole grain intake with all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis from prospective cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018 Jan;72(1):57-65. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2017.149.