COVID-19, Immune Dysregulation, and Cancer Risk

Understanding the Complex Relationship Between Viral Infection, Vaccination, and Cancer; and the Gift of Herbal Medicine The COVID-19 pandemic has raised important questions about the

Understanding the Complex Relationship Between Viral Infection, Vaccination, and Cancer; and the Gift of Herbal Medicine The COVID-19 pandemic has raised important questions about the

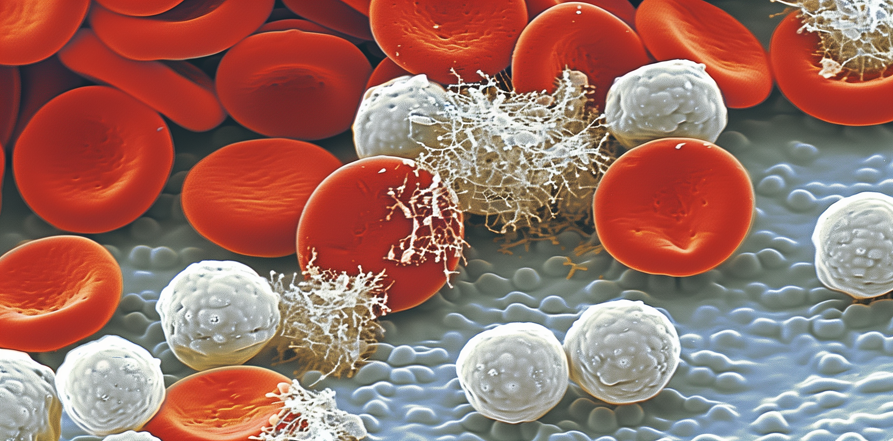

By Donnie Yance Cancer isn’t merely uncontrolled cell growth, it’s a profound disruption of the body’s metabolic pathways. At its core, cancer represents a reprogramming

By Donnie Yance Questioning Conventional Screening Approaches According to the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) analysis of two major randomized clinical trials, routine

Why You Should Think Twice About Neulasta Or Neupogen When On Chemotherapy By Donnie Yance “The most telling and profound way of describing the evolution

Several years ago, I did a 2-part blog on the dangers of sunscreens. They have some good information, and the links are below. The Dangers

Around 35 years ago, I founded my first clinic in Norwalk, CT. It was there that I met a young breast cancer patient who forever

Gankyrin and Cancer A better understanding of Gankyrin, glutamine, and glutamate production is crucial for cancer patients and their doctors. Cancer develops when cells start

Improving Cell Metabolism with Botanical Compounds Healthy cell metabolism or normal cellular metabolism is when the chemical reactions that occur in living cells are working

Before I dive into my personal perspective on cancer screening, I want to address the dire state of healthcare in our country. A recently published